|

Leah Brogan, Angela Pollard, & Naomi Goldstein This is the final post in our Spencer Foundation Building a “Prison-to-School Pipeline” series on the JJR&R Lab website.

Juvenile justice stakeholder participants at the “Prison-to-School Pipeline” convening, hosted by the Juvenile Justice Research and Reform (JJR&R) Lab and sponsored by the Spencer Foundation, generated solutions their agencies could quickly enact to address obstacles to successfully reintegrating youth into schools following confinement in juvenile detention or post-adjudication placement facilities. They particularly emphasized addressing “low-hanging fruit”—those obstacles they could quickly and easily address. These practitioners, policy advocates, and researchers then identified important outcomes they would hope to see if they built and implemented an effective prison-to-school pipeline and potential methods of measuring these outcomes over time. They recommended:

Research specifically addressing the school re-entry process for youth returning from confinement is limited.[1] Research-practice partnerships established through this convening can stimulate richer investigation into the gaps of the prison-to-school pipeline. Through a community-based, participatory-action research lens, researchers in attendance actively listened to practitioners’ ideas regarding where improvement is needed in the prison-to-school pipeline and then collaboratively generated methods of measuring relevant outcomes for youth, systems, and communities. Although much work remains to be done, this convening stimulated diverse inter-agency collaboration to translate stakeholder concerns into actionable strategies to measure some key outcomes to evaluate efforts to facilitate school re-entry, engagement, and graduation for youth returning from confinement. [1] Snodgrass Rangel, V., Hein, S., Rotramel, C., & Marquez, B. (2020). A researcher-practitioner agenda for studying and supporting youth reentering school after involvement in the juvenile justice system. Educational Researcher, 49(3), 212-219. Doi: 10.3102/0013189X20909822

2 Comments

Leah Brogan, Angela Pollard, Rena Kreimer, & Naomi Goldstein

This post is part of our Spencer Foundation Convening Recap series on the JJR&R Lab website. Roughly 25% of justice-involved youth drop-out of school within the six months following release from confinement, and only 15% of ninth graders who were confined graduate high school within four years.[1] Philadelphia and national stakeholders came together virtually last month (see blog post below) to build a “prison-to-school pipeline” model as part of a 3-day convening. Stakeholders at this convening, hosted by the Juvenile Justice Research and Reform (JJR&R) Lab at Drexel University and sponsored by the Spencer Foundation, identified barriers youth face when transitioning from confinement to community schools. Barriers identified included challenges at multiple levels, including:

Convening participants noted the following challenges as among the greatest obstacles to successfully reintegrating youth following juvenile justice confinement and supporting them on their paths to graduation:

Stakeholders also identified a subset of these challenges that seemed to be low-hanging fruit—areas they believed their respective agencies and systems could quickly and efficiently address following the convening. For example, convening participants identified multiple agencies that should be present at a youth’s discharge planning meeting to facilitate rapid re-entry into schools upon discharge from confinement. Participants also identified that the delays in transferring a youth’s academic records between placements and schools may result in a youth’s assignment to an inappropriate academic setting. To rectify both of these issues, the identified agencies collaborated to enhance discharge planning meetings by including all relevant stakeholder agencies at the meeting and bringing the youth’s placement academic records to the discharge planning meeting. Examples of other low-hanging fruit identified by stakeholders included:

Identifying these challenges and generating solutions for more successful youth reintegration reflect both the strength of the stakeholder collaboration sparked during this convening and the growing momentum for change within Philadelphia’s youth serving systems. Check out our next post for potential outcomes associated with building a prison-to-school pipeline and methods of measuring changes in these outcomes over time. [1]U.S. Department of Education Civil Rights Data Collection (2016). Database. Retrieved from http://ocrdata.ed.gov//. By: Angela Pollard, Rena Kreimer, Leah Brogan, & Naomi Goldstein In Philadelphia, only 36% of students involved in the juvenile justice system graduate from high school. Unfortunately, this collateral consequence of juvenile justice system involvement is not limited to students in Philadelphia—successful reenrollment and reengagement of students in school following discharge from a juvenile justice facility is a nationwide challenge, and disproportionately impacts youth of color.[1],[2] Confinement in juvenile justice facilities can create high barriers for students to overcome to re-engage with school, such as inadequate educational programming offered in juvenile justice facilities that leaves students ill-prepared for the academic rigors of mainstream school settings, school re-entry policies that segregate students returning from confinement into disciplinary alternative education programs, and delays in transferring academic records between facilities and schools that result in students being barred from re-entry completely (for more details on these barriers, see Beebe & Rynders [2020], Carter [2018], and Southern Education Foundation [2014]). Building on existing collaborative efforts in Philadelphia to support youth with or at-risk of justice system involvement (see here for a key initiative to dismantle the school-to-prison pipeline), the Juvenile Justice Research and Reform (JJR&R Lab) at Drexel University, with support from the Spencer Foundation, convened practitioners, advocates, community members, and researchers virtually across three days to develop a best-practice model for supporting the educational success of youth returning to their communities from juvenile justice confinement. During this convening, local Philadelphia and national stakeholders worked to develop a prison-to-school pipeline model through active working groups and discussions and to set a strategic agenda led by cross-systems partnerships. A variety of individuals contributed their expertise and willingness to collaborate at the convening, with representatives from:

This diverse group of convening participants jointly identified the most important challenges to address in successfully re-enrolling youth in schools after they return home to their communities from juvenile justice confinement, re-engaging them in these educational environments, and supporting them on their paths toward graduation. Some of these challenges included:

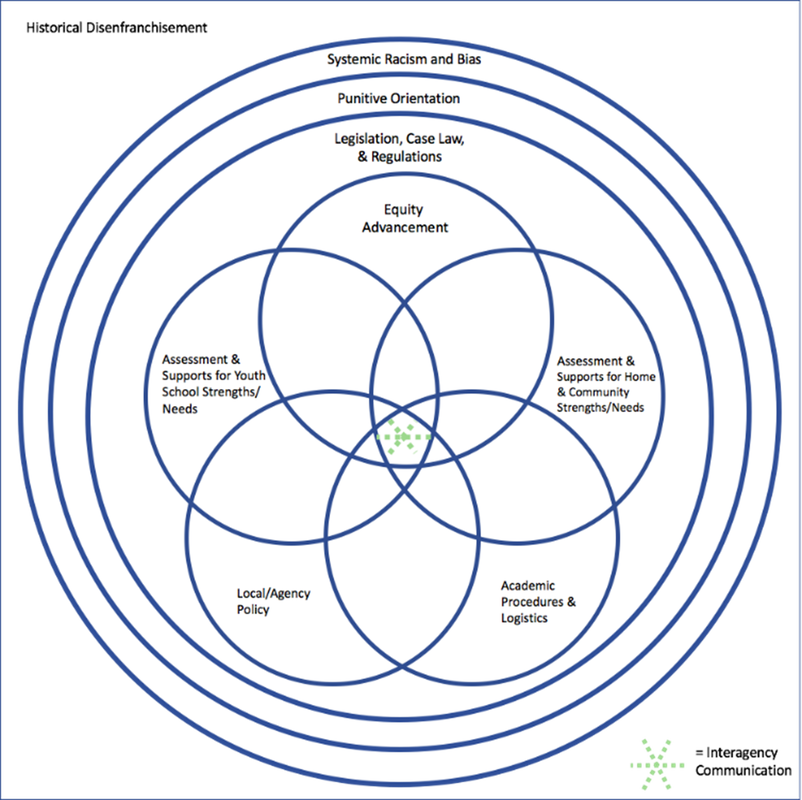

Additionally, this group of stakeholders identified how these challenges fit into a comprehensive model for change. The model (pictured below) calls for practitioners, policy makers, advocates, and researchers to address the obstacles to successful school re-integration within the broader context of historical disenfranchisement, systemic racism, the punitive orientations of both the juvenile justice and school systems, and existing regulations. To address systemic barriers and support youths’ successful reintegration and their progress toward graduation, the group identified five primary areas to address, which are depicted in the five concentric circles at the center of the model. The group also highlighted interagency communication and oversight as essential to achieving meaningful system change. Check out our next post for a deeper dive into the specific challenges identified and how participants planned to address these challenges in Philadelphia and beyond.

[1] Singer, S., Mozaffar, N., Burdick, K., Gardella, J., Kreimer, R., Chan, W., & Goldstein, N. (March 2019). Difficulties transferring academic credits from juvenile justice facilities: Understanding the scope and source of the problem and implications for students. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Psychology-Law Society, Portland, Oregon. [2] Weatherspoon, F. (2014). African-American males and the US justice system of marginalization: A national tragedy. Palgrave Pivot, New York. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137408433_1 The interdisciplinary Juvenile Justice Research and Reform Lab (JJR&R Lab) at Drexel University works to promote best practices in the juvenile justice system by more closely aligning juvenile justice policies and procedures with adolescents' developmental capacities. For more than 20 years, Dr. Naomi Goldstein’s JJR&R Lab has conducted innovative research and partnered with public agencies to enact real-world, large-scale, systemic changes within and for the juvenile justice system that produce more just and equitable outcomes for youth and communities.

In 2021, we are thrilled to launch this blog as a space to share more about our ongoing work, research, and partnerships. For example, we recently hosted a virtual convening with local and national experts to enhance methods of reintegrating students into school and educational settings following juvenile justice system involvement. We will publish a series of posts in the upcoming weeks to document and share some of the insights and takeaways from those valuable discussions, which will serve as a foundation for future conversations and collaborations. We also plan to use this blog as a tool to share more about JJR&R Lab’s work conducting and using high quality research to: • Improve youth outcomes, • Improve outcomes for communities, • Inform policy and practice, • Partner with communities, and • Generate local and global impacts. We look forward to sharing more in the coming weeks! |

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed