|

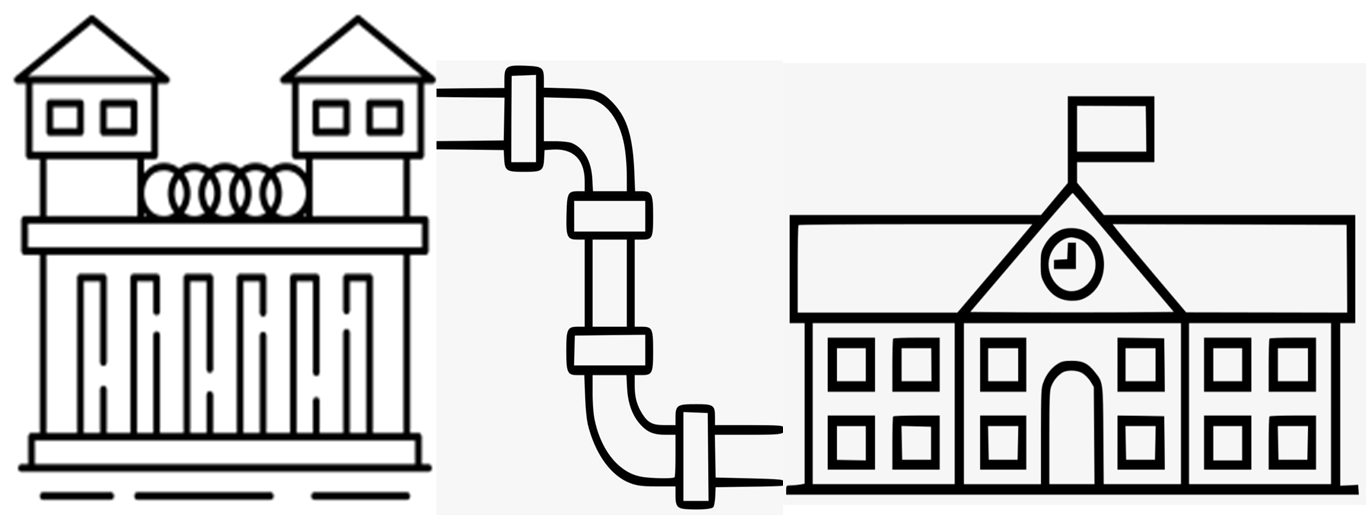

Leah Brogan, Angela Pollard, & Naomi Goldstein This is the final post in our Spencer Foundation Building a “Prison-to-School Pipeline” series on the JJR&R Lab website.

Juvenile justice stakeholder participants at the “Prison-to-School Pipeline” convening, hosted by the Juvenile Justice Research and Reform (JJR&R) Lab and sponsored by the Spencer Foundation, generated solutions their agencies could quickly enact to address obstacles to successfully reintegrating youth into schools following confinement in juvenile detention or post-adjudication placement facilities. They particularly emphasized addressing “low-hanging fruit”—those obstacles they could quickly and easily address. These practitioners, policy advocates, and researchers then identified important outcomes they would hope to see if they built and implemented an effective prison-to-school pipeline and potential methods of measuring these outcomes over time. They recommended:

Research specifically addressing the school re-entry process for youth returning from confinement is limited.[1] Research-practice partnerships established through this convening can stimulate richer investigation into the gaps of the prison-to-school pipeline. Through a community-based, participatory-action research lens, researchers in attendance actively listened to practitioners’ ideas regarding where improvement is needed in the prison-to-school pipeline and then collaboratively generated methods of measuring relevant outcomes for youth, systems, and communities. Although much work remains to be done, this convening stimulated diverse inter-agency collaboration to translate stakeholder concerns into actionable strategies to measure some key outcomes to evaluate efforts to facilitate school re-entry, engagement, and graduation for youth returning from confinement. [1] Snodgrass Rangel, V., Hein, S., Rotramel, C., & Marquez, B. (2020). A researcher-practitioner agenda for studying and supporting youth reentering school after involvement in the juvenile justice system. Educational Researcher, 49(3), 212-219. Doi: 10.3102/0013189X20909822

2 Comments

Leah Brogan, Angela Pollard, Rena Kreimer, & Naomi Goldstein

This post is part of our Spencer Foundation Convening Recap series on the JJR&R Lab website. Roughly 25% of justice-involved youth drop-out of school within the six months following release from confinement, and only 15% of ninth graders who were confined graduate high school within four years.[1] Philadelphia and national stakeholders came together virtually last month (see blog post below) to build a “prison-to-school pipeline” model as part of a 3-day convening. Stakeholders at this convening, hosted by the Juvenile Justice Research and Reform (JJR&R) Lab at Drexel University and sponsored by the Spencer Foundation, identified barriers youth face when transitioning from confinement to community schools. Barriers identified included challenges at multiple levels, including:

Convening participants noted the following challenges as among the greatest obstacles to successfully reintegrating youth following juvenile justice confinement and supporting them on their paths to graduation:

Stakeholders also identified a subset of these challenges that seemed to be low-hanging fruit—areas they believed their respective agencies and systems could quickly and efficiently address following the convening. For example, convening participants identified multiple agencies that should be present at a youth’s discharge planning meeting to facilitate rapid re-entry into schools upon discharge from confinement. Participants also identified that the delays in transferring a youth’s academic records between placements and schools may result in a youth’s assignment to an inappropriate academic setting. To rectify both of these issues, the identified agencies collaborated to enhance discharge planning meetings by including all relevant stakeholder agencies at the meeting and bringing the youth’s placement academic records to the discharge planning meeting. Examples of other low-hanging fruit identified by stakeholders included:

Identifying these challenges and generating solutions for more successful youth reintegration reflect both the strength of the stakeholder collaboration sparked during this convening and the growing momentum for change within Philadelphia’s youth serving systems. Check out our next post for potential outcomes associated with building a prison-to-school pipeline and methods of measuring changes in these outcomes over time. [1]U.S. Department of Education Civil Rights Data Collection (2016). Database. Retrieved from http://ocrdata.ed.gov//. |

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed