|

By: Angela Pollard, Rena Kreimer, Leah Brogan, & Naomi Goldstein In Philadelphia, only 36% of students involved in the juvenile justice system graduate from high school. Unfortunately, this collateral consequence of juvenile justice system involvement is not limited to students in Philadelphia—successful reenrollment and reengagement of students in school following discharge from a juvenile justice facility is a nationwide challenge, and disproportionately impacts youth of color.[1],[2] Confinement in juvenile justice facilities can create high barriers for students to overcome to re-engage with school, such as inadequate educational programming offered in juvenile justice facilities that leaves students ill-prepared for the academic rigors of mainstream school settings, school re-entry policies that segregate students returning from confinement into disciplinary alternative education programs, and delays in transferring academic records between facilities and schools that result in students being barred from re-entry completely (for more details on these barriers, see Beebe & Rynders [2020], Carter [2018], and Southern Education Foundation [2014]). Building on existing collaborative efforts in Philadelphia to support youth with or at-risk of justice system involvement (see here for a key initiative to dismantle the school-to-prison pipeline), the Juvenile Justice Research and Reform (JJR&R Lab) at Drexel University, with support from the Spencer Foundation, convened practitioners, advocates, community members, and researchers virtually across three days to develop a best-practice model for supporting the educational success of youth returning to their communities from juvenile justice confinement. During this convening, local Philadelphia and national stakeholders worked to develop a prison-to-school pipeline model through active working groups and discussions and to set a strategic agenda led by cross-systems partnerships. A variety of individuals contributed their expertise and willingness to collaborate at the convening, with representatives from:

This diverse group of convening participants jointly identified the most important challenges to address in successfully re-enrolling youth in schools after they return home to their communities from juvenile justice confinement, re-engaging them in these educational environments, and supporting them on their paths toward graduation. Some of these challenges included:

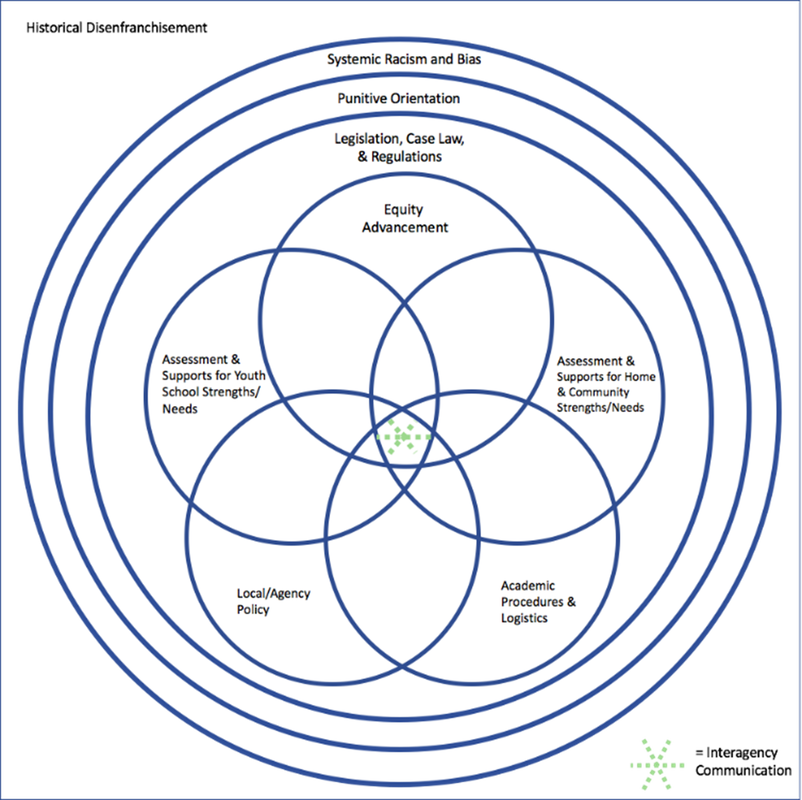

Additionally, this group of stakeholders identified how these challenges fit into a comprehensive model for change. The model (pictured below) calls for practitioners, policy makers, advocates, and researchers to address the obstacles to successful school re-integration within the broader context of historical disenfranchisement, systemic racism, the punitive orientations of both the juvenile justice and school systems, and existing regulations. To address systemic barriers and support youths’ successful reintegration and their progress toward graduation, the group identified five primary areas to address, which are depicted in the five concentric circles at the center of the model. The group also highlighted interagency communication and oversight as essential to achieving meaningful system change. Check out our next post for a deeper dive into the specific challenges identified and how participants planned to address these challenges in Philadelphia and beyond.

[1] Singer, S., Mozaffar, N., Burdick, K., Gardella, J., Kreimer, R., Chan, W., & Goldstein, N. (March 2019). Difficulties transferring academic credits from juvenile justice facilities: Understanding the scope and source of the problem and implications for students. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Psychology-Law Society, Portland, Oregon. [2] Weatherspoon, F. (2014). African-American males and the US justice system of marginalization: A national tragedy. Palgrave Pivot, New York. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137408433_1

7 Comments

8/2/2022 11:09:54 am

The model calls for practitioners, policy makers, advocates, and researchers to address the obstacles to successful school re-integration within the broader context of historical disenfranchisement, I’m so thankful for your helpful post!

Reply

Naomi Goldstein

8/2/2022 07:40:08 pm

You’re welcome, and thank you for the great summary of this model. We were inspired by the eagerness of multi-system stakeholders to work together to identify barrier and solutions to this widespread and very challenging issue.

Reply

8/2/2022 11:56:21 am

Confinement in juvenile justice facilities can create high barriers for students to overcome to re-engage with school, such as inadequate educational programming offered in juvenile justice facilities that leaves students ill-prepared Thank you for making this such an awesome post!

Reply

Naomi Goldstein

8/2/2022 07:37:20 pm

Thanks so much for the kind words. Kids coming out of facilities need and deserve help accessing school. It’s great to see people caring about this topic!

Reply

1/14/2023 05:30:18 am

During this convening, local Philadelphia and national stakeholders worked to develop a prison to school pipeline model through active working, Thank you for sharing your great post!

Reply

12/10/2023 05:08:23 pm

It's disheartening to learn that in Philadelphia, just 36% of students involved in the juvenile justice system manage to graduate from high school. This startling statistic, as highlighted in the JJR&R Lab Blog, sheds light on a critical issue that extends beyond Philadelphia's borders.

Reply

7/25/2024 01:37:40 am

What is the goal of the Juvenile Justice Research and Reform (JJR&R Lab) at Drexel University in collaboration with the Spencer Foundation, and how did they aim to achieve it?

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed