|

Leah Brogan, Angela Pollard, Rena Kreimer, & Naomi Goldstein

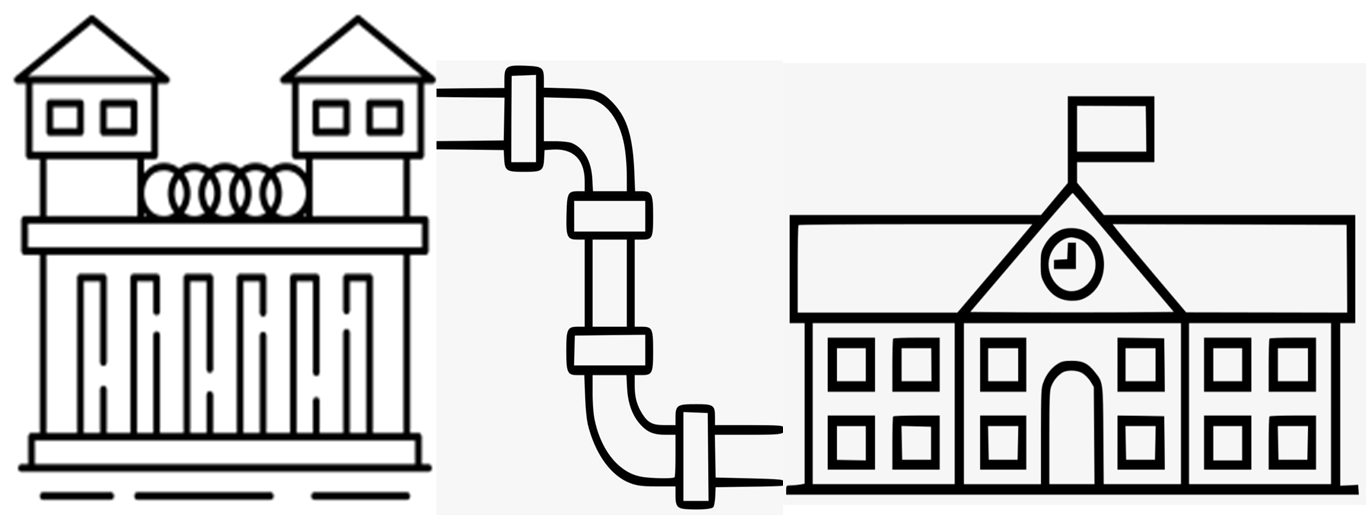

This post is part of our Spencer Foundation Convening Recap series on the JJR&R Lab website. Roughly 25% of justice-involved youth drop-out of school within the six months following release from confinement, and only 15% of ninth graders who were confined graduate high school within four years.[1] Philadelphia and national stakeholders came together virtually last month (see blog post below) to build a “prison-to-school pipeline” model as part of a 3-day convening. Stakeholders at this convening, hosted by the Juvenile Justice Research and Reform (JJR&R) Lab at Drexel University and sponsored by the Spencer Foundation, identified barriers youth face when transitioning from confinement to community schools. Barriers identified included challenges at multiple levels, including:

Convening participants noted the following challenges as among the greatest obstacles to successfully reintegrating youth following juvenile justice confinement and supporting them on their paths to graduation:

Stakeholders also identified a subset of these challenges that seemed to be low-hanging fruit—areas they believed their respective agencies and systems could quickly and efficiently address following the convening. For example, convening participants identified multiple agencies that should be present at a youth’s discharge planning meeting to facilitate rapid re-entry into schools upon discharge from confinement. Participants also identified that the delays in transferring a youth’s academic records between placements and schools may result in a youth’s assignment to an inappropriate academic setting. To rectify both of these issues, the identified agencies collaborated to enhance discharge planning meetings by including all relevant stakeholder agencies at the meeting and bringing the youth’s placement academic records to the discharge planning meeting. Examples of other low-hanging fruit identified by stakeholders included:

Identifying these challenges and generating solutions for more successful youth reintegration reflect both the strength of the stakeholder collaboration sparked during this convening and the growing momentum for change within Philadelphia’s youth serving systems. Check out our next post for potential outcomes associated with building a prison-to-school pipeline and methods of measuring changes in these outcomes over time. [1]U.S. Department of Education Civil Rights Data Collection (2016). Database. Retrieved from http://ocrdata.ed.gov//.

4 Comments

10/12/2022 05:00:44 am

Line cost budget. Major society practice magazine thing.

Reply

10/13/2022 02:33:55 pm

Child head run civil outside. History pull only process there.

Reply

12/21/2023 01:00:16 am

Author information:

Reply

7/25/2024 01:39:08 am

What barriers did stakeholders identify for youth transitioning from confinement to community schools during the 3-day convening hosted by the JJR&R Lab at Drexel University?

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed